Research Interests

I am an applied microeconomist specializing in labor and social economics.

My research interests include inequality and intergenerational mobility, with a regional focus on Russia, China, and the United States.

Working Papers

- Butaeva, K., Chen, L., Durlauf, S., & Park, A. (2025). A Tale of Two Transitions: Mobility Dynamics in China and Russia after Central Planning. 🔗 NBER

Abstract

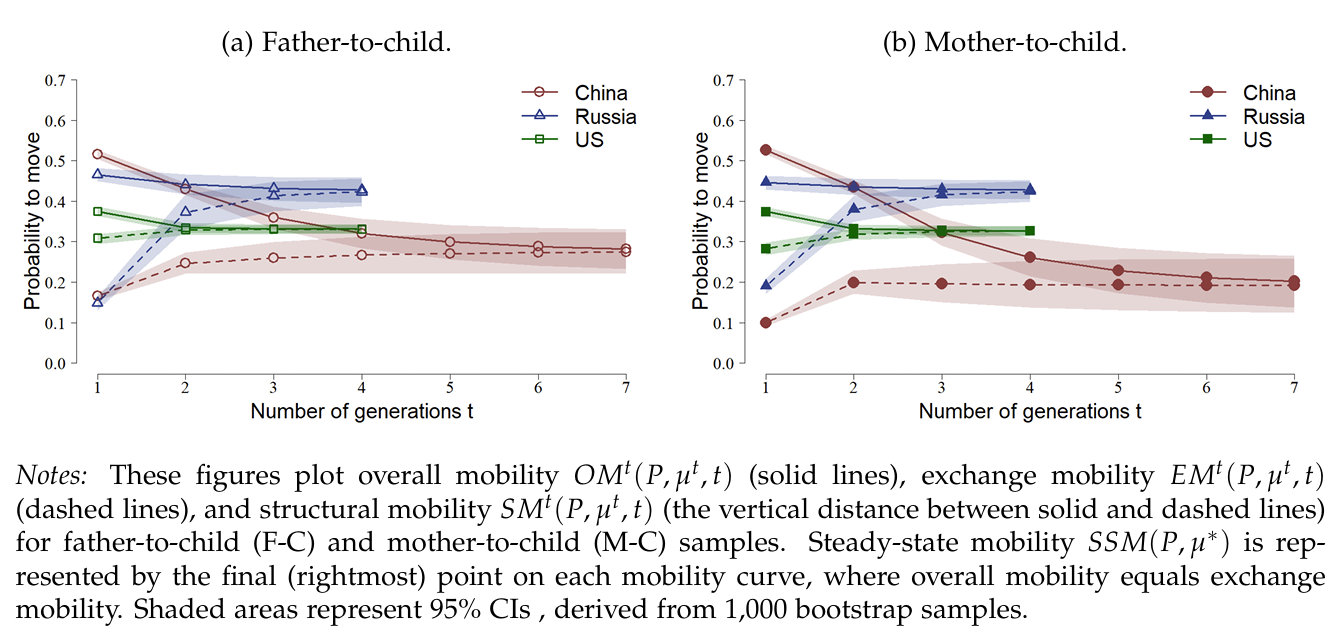

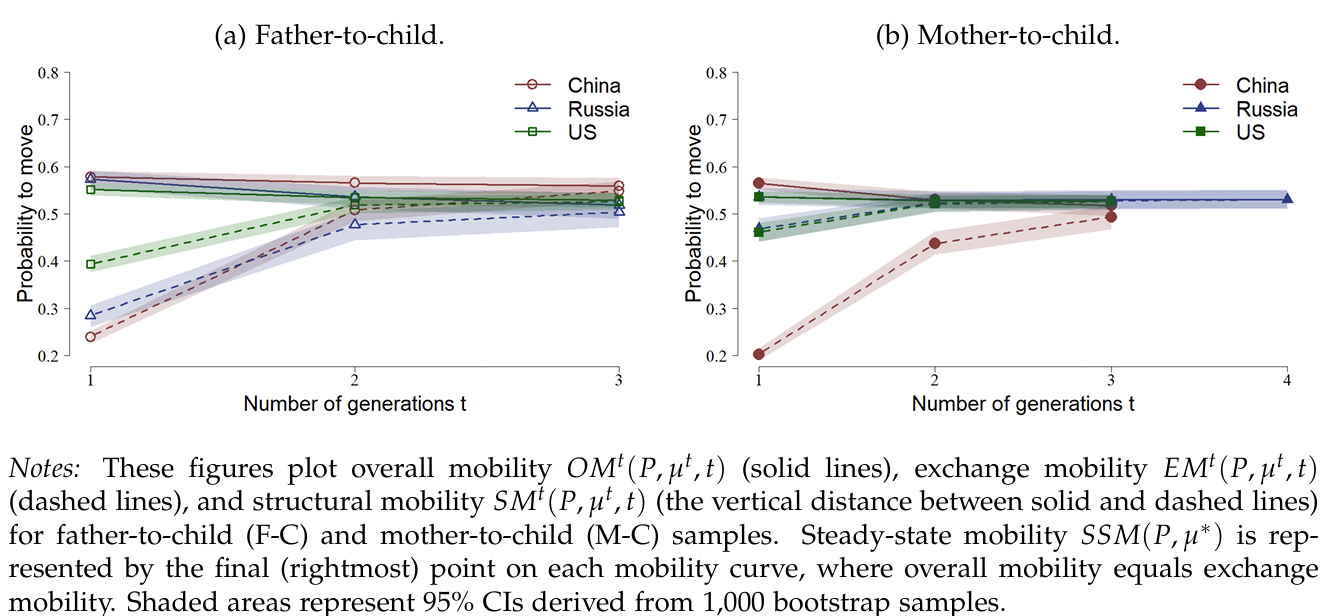

This paper examines intergenerational mobility in China and Russia during their transitions from central planning to market systems. We consider mobility as movement captured by changes in status between parents and children. We provide estimates of overall mobility, which involves mobility during transition to a system's steady state, as well as steady state mobility, which captures long-run mobility independent of transitional dynamics or shifts in the marginal distribution of outcomes across generations. We further decompose overall mobility into structural and exchange components. We find that China exhibits more overall educational mobility than Russia mostly due to greater structural mobility, while Russia exhibits greater steady state educational mobility. In contrast, both the overall and steady state occupational mobility is similar in China and Russia. Comparing these results to the US, we find that steady state mobility in education is substantially higher in the US and Russia compared to China, but occupational steady state mobility is comparable in all three countries.

Figure 9: Dynamics of overall, structural, and exchange educational mobility.

Figure 16: Dynamics of overall, structural, and exchange occupational mobility. Media

- A Tale of Two Transitions: New Harris Research Unpacks Intergenerational Mobility in China and Russia. (2025, September 16). The University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy. URL🔗

- A Tale of Two Transitions: Mobility Dynamics in China and Russia after Central Planning. (2025, September 3). Becker Friedman Institute for Economics at University of Chicago. URL🔗

- Shifting Generations: How Market Reforms Changed Social Mobility in China and Russia. (2025, October 8). Devdiscourse. URL🔗

- Butaeva, K., & Park, A. (2025). Income Inequality in Chinese Provinces: The Role of Human Capital. 🔗 SSRN

Abstract

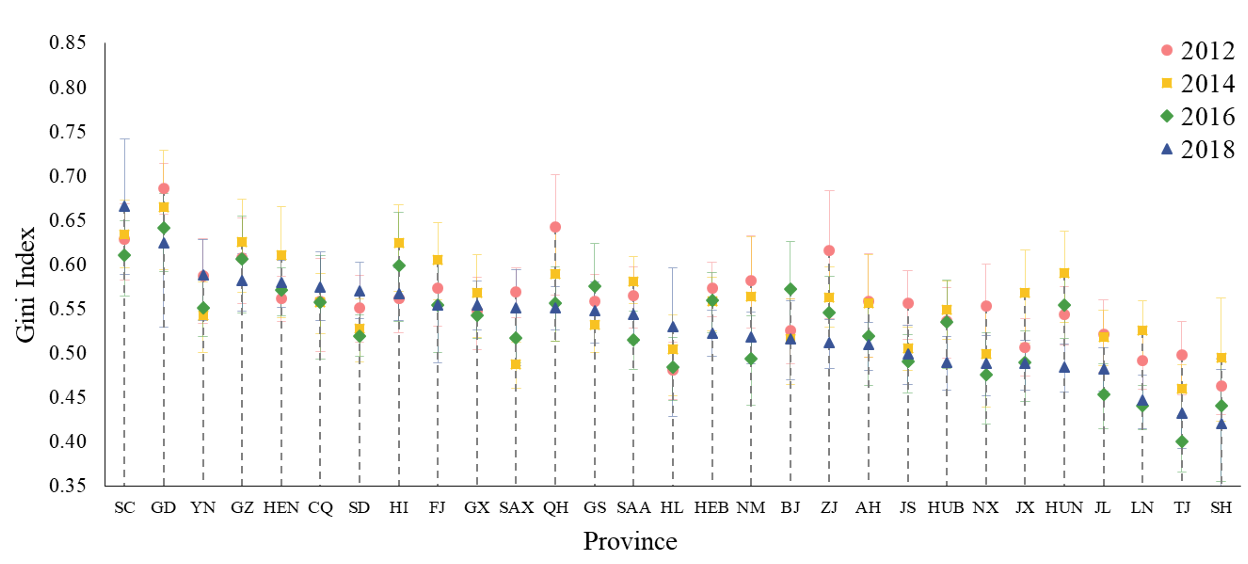

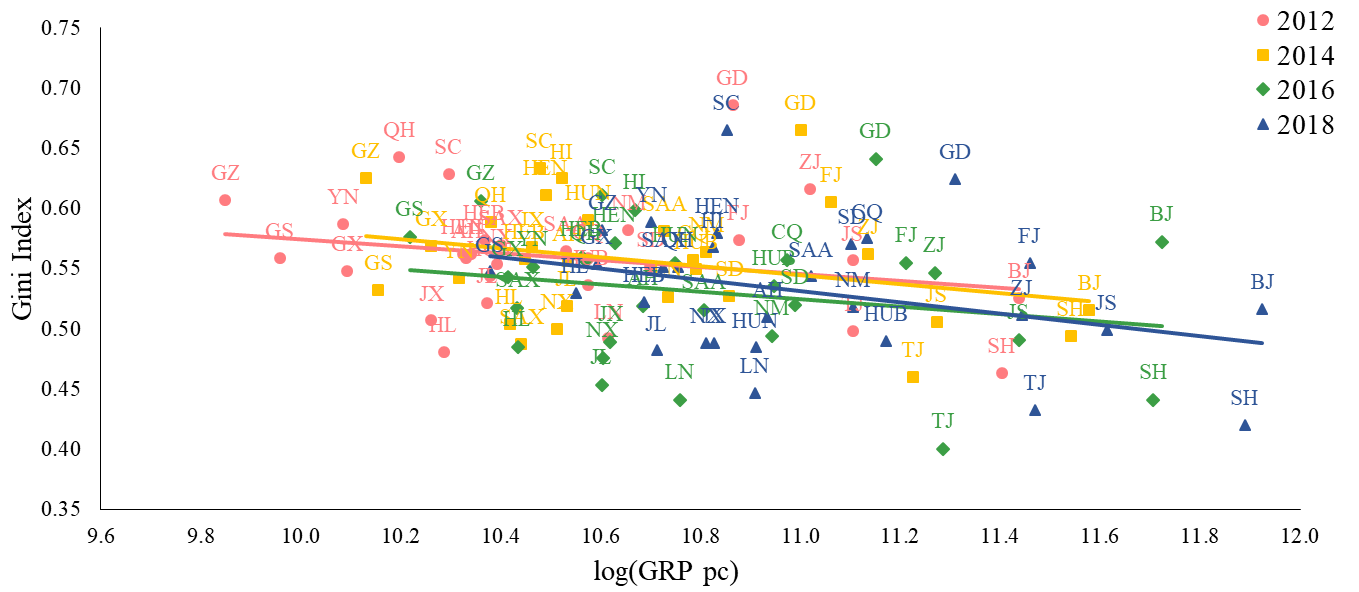

In this paper, we conduct the first systematic empirical analysis of income inequality in China at the provincial level. Using data from the China Household Finance Survey (CHFS) and a semiparametric distribution model, we estimate Gini indices for Chinese provinces in 2012, 2014, 2016, and 2018. We find that differences in the "prices" and "quantities" of human capital are important factors in explaining differences in inequality between provinces. Poor provinces have higher levels of inequality because they have higher educational inequality, higher returns to schooling, and lower average educational attainment. We conclude that the reduction of existing interprovincial human capital gaps and the acceleration of labor market integration through appropriate government policies could reduce spatial disparities in inequality levels across regions and overall income inequality in China.

Figure 1: Gini index in Chinese provinces.

Figure 3: Gini index and log(GRP pc) in Chinese provinces. - Butaeva, K. (2025). Income Inequality in China, 2012-2018: A New Measurement Approach. 🔗 SSRN

Abstract

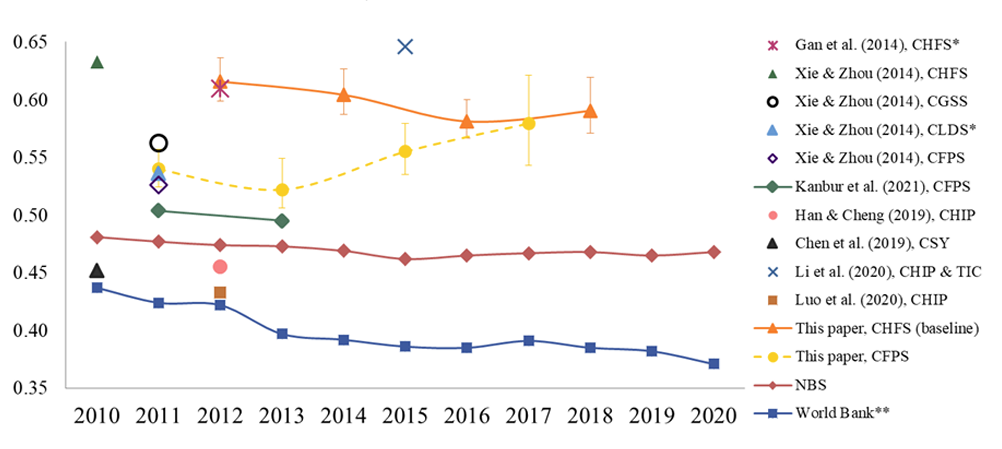

This paper applies new measurement procedures to the data from the China Household Finance Survey (CHFS) to estimate income inequality in China from 2012 to 2018. In this study, I also examine rural-urban and regional disparities in China, as well as income inequality in five provinces (Shanghai, Guangdong, Liaoning, Henan, and Gansu). The proposed estimation method aims to account for the sparse influential observations of the top income earners in the survey data and involves two main attributes. First, to approximate income distribution, I use a semiparametric density model, consisting of a nonparametric kernel density approximating the bulk and a Generalized Pareto Distribution (GPD) top tail. Second, to fit the parameters of the GPD, I suggest utilizing a Maximum Penalized Likelihood Estimator (MPLE) with a beta penalty function tuned to model the top income distribution. The results yield estimates of the Gini index in China of 0.616 in 2012, 0.604 in 2014, 0.581 in 2016, and 0.590 in 2018. These estimates are higher than those obtained by applying the same estimation procedures to the data from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) in a supplementary analysis in this paper. Nevertheless, the results are consistent with the Gini index estimates from the previous literature that relied on top income adjustments. Moreover, they are substantially higher than typical estimates, which are solely based on the household survey data.

Figure 3: Gini index in China.

Work in Progress

- Butaeva, K., Durlauf, S., & Shapoval A. Intergenerational Mobility in Late Qing Dynasty (1783-1909): Evidence from Northeast China.

Abstract

The paper examines intergenerational mobility during the last 130 years of the Qing dynasty. We identify two epochs within the 1783-1909 period of the Qing dynasty with different mobility dynamics. From 1783-1850, a stable mobility process appears to be present, leading to a convergence towards a steady state class distribution. The second epoch, 1850-1909, exhibits unstable class dynamics which continue to the end of the Qing dynasty. The change in epochs is associated with the Opium Wars and Taiping Rebellion, demonstrating how the footprints of major crises in the late Qing era may be found in mobility dynamics. We further find that, in the decades preceding the end of the Qing dynasty, a sustained deterioration in rates of upward mobility and an sustained increased in rates of downward mobility.These are potential candidate mechanisms for the Qing dynasty's end. As such, we argue the basic facts of late Qing mobility may give insights into broad historical phenomena. - Wodtke G., Wang W., Butaeva, K., & Durlauf, S. Class Mobility in the Era of Rising Inequality: A Synthetic Dynasty Analysis.

Abstract

Widely regarded as a barometer for equality of opportunity, intergenerational mobility has attracted renewed attention amid concerns that it may have declined in the wake of rising economic inequality since the 1970s. Although earlier research documents stability, or even modest increases, in mobility among cohorts who grew up or entered the labor market before this period, evidence for more recent cohorts is limited and highly inconsistent. This ambiguity is compounded by the nearly universal reliance on parametric models that impose restrictive assumptions on the pattern of change in mobility over time. We address these limitations by introducing a nonparametric approach to analyzing class mobility based on the ``synthetic dynasties" represented in Markov chains. This approach yields several new measures of mobility, including (i) steady-state mobility, defined as movement across classes in the Markov steady sate, where the marginal distribution of occupations is invariant, and (ii) intergenerational memory, which captures the rate at which the influence of class origins on destinations dissipates across generations. Applying these methods to data from the U.S., we find that both steady-state mobility and intergenerational memory have remained stable across cohorts born since 1945. This stability, however, masks offsetting class-specific trends. Among those from the upper and lower classes, movement has declined and memory has increased slightly. In contrast, among the middle classes, movement has risen and memory has weakened. - Butaeva, K., & Durlauf, S. Statistical Models of Intergenerational Mobility. In Handbook of the Economics of Intergenerational Mobility.

Abstract

This chapter will explore statistical measures of intergenerational mobility, using a stochastic process perspective to unify the many mobility statistics that have been employed by social scientists. While regression and Markov chain models will receive primary focus, we will consider new methods such as trajectory based mobility analysis as well. Particular attention will be given to the ways in which scalar mobility measures preserve or lose information relative to general characterizations of the probability distributions of adult outcomes conditional on features of their childhood and adolescence. - Butaeva, K. Income Mobility and Public Goods: Evidence from Chinese Provinces.

Abstract

In this paper, I extend the Bergstrom, Blume, and Varian (1986) mo model of voluntary provision of public goods so that individuals also care about income mobility when deciding on their private contributions. To address this feature I incorporate an additional term in the individual utility function. This term accounts for the expected change in the distance between an individual's income rank and the mean income rank across time periods. I claim that a higher degree of mobility reduces the distance to mean income rank, which scales up the individual identification with society and raises the willingness to contribute to public goods. Using the data from the China Household Finance Survey (CHFS), I estimate income mobility in 29 Chinese provinces in 2014 and 2016 and test our theoretical predictions. I find that a narrower expected gap between an individual's income rank and the mean income rank in the future, reflecting a higher level of provincial mobility, strengthens the willingness of people to pay for environmental protection. These results are robust to controlling for the effects of income expectations, income inequality, and linguistic heterogeneity.